Hello friends, and Happy New Year. I hope 2024 is treating you well so far.

Last month, I finished Jonathan Eig’s magnificent King: A Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023), and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. King is the first comprehensive biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. to be published in several decades. It’s a great read, and an important one. Eig consulted all the previously available material, plus FBI files that have been declassified only recently. That new information, as Eig points out, contains no evidence to support King’s supposed sympathies for communism (which were alleged during his lifetime). But the newly released files do reveal much about King’s marital infidelities as well as the FBI’s single-minded determination to discredit him along with much of the civil rights movement. J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI and President Lyndon Johnson became obsessed with undermining Martin Luther King, Jr. They come off quite badly in Eig’s rendering.

It’s upsetting, to say the least, and disturbing. In my naïveté, I had always thought Johnson was wholly committed to King and civil rights, but King suggests I was wrong. Or rather, I realize now that Johnson’s apparent commitment was politically nuanced and circumscribed by contingencies. Perhaps it’s time for me to read all four volumes of Robert Caro’s biographies of Johnson.

I had expected to like Eig’s book, but I had not expected to love it, if only because I was slightly resistant to what I thought was another “Great Man” biography. And it is a Great Man biography, because Martin Luther King, Jr. was a great man — but a man made great both by a slow-growing internal conviction and by the circumstances he lived in; by a movement that, through a confluence of timing and need, elected him as its spokesperson not least because he married words and rhythm to the drive that so many Black people felt in the 1950s and 1960s. King crafted the song of liberty. The cadence of his speaking voice was honed in the church choirs his mother led. As a child, Martin Luther King, Jr. loved to sing. As a grown man, he gave the movement its moral compass and its narrative of love through musicality, through the storytelling that is inherent in song.

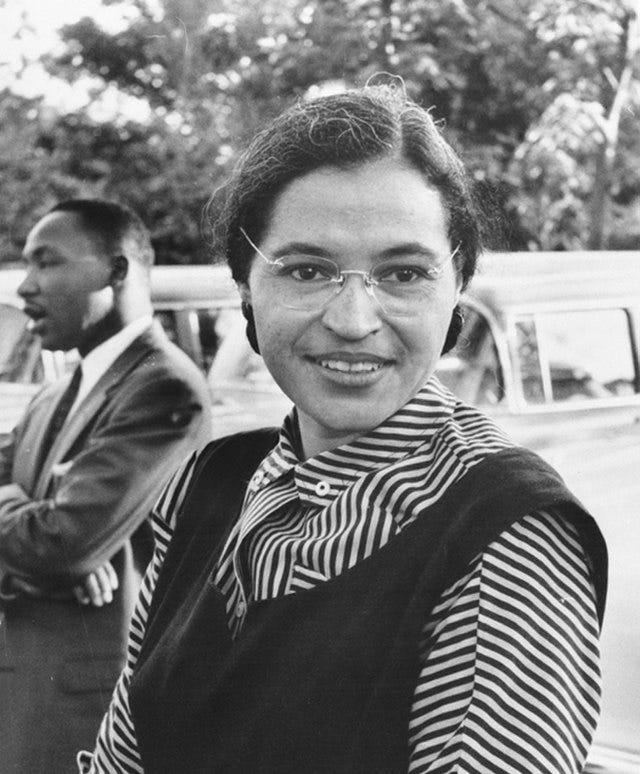

But the real reason I loved King was Eig’s treatment of Coretta Scott King. And, in fact, his treatment of all the women working behind the scenes in the civil rights movement. King was surrounded by women and drew from them. As Eig explains, it was King’s grandmother to whom he was closest as a young child. It was his mother who led the choir at Ebenezer Baptist church, who gave him his early love of music, and inspired the rhythms of his speeches. It was Rosa Parks who was a spark in the early civil rights movement, before King himself; it was Rosa who energized King in Montgomery. Rosa Parks is remembered for her heroic role on that Alabama bus, but she was also a strategic and intuitive organizer, one who wanted a greater role in the movement, but was denied one by the entrenched sexist attitude of the Southern Baptist Church.

The same holds true for Coretta Scott King. It was Coretta who was involved in civil rights before her husband. It was Coretta who introduced Martin to new ways of thinking and organizing. A Eig tells us, “at that point in their lives [when they were dating], Coretta had more experience than Martin as an activist.” According to Harry Belafonte, it was Martin who “‘stepped into her space.’” Coretta was a sharply intelligent woman and an exceptionally talented singer with a promising career. She gave up a lot when she married Martin Luther King, Jr. It was made clear to her, after they married and after Martin found himself with the excruciatingly difficult task of leading a revolution in civil rights, that the spouse was the most important part she could play — both for Martin and for the movement.

She was the wife. “‘That was an adjustment I had to make,’” Coretta would later say. “‘I believe I made it very well.’” (109)

She was faithful; he was not. “‘He loved his wife,’’ said one friend. “‘But he also, he loved some other folks, too.’” (242) And sometimes in that faithlessness, he was unabashedly cruel.

Of course, she wasn’t ‘just the wife.’ Coretta considered herself Martin’s collaborator, as did most of their colleagues. But Coretta yearned for an even larger part in the movement, as Eig takes pains to show.

He develops the sub-story of Coretta carefully, planting the seeds early on in the book. Eig doesn’t tell you what happens to Coretta. He shows you, in part through writing technique. Eig describes her early life, her education and career aspirations. She was a fabulous student. He explains that she was not Martin’s first love, nor even his first choice of wife, and how it was that they came to be married. Then, midway through chapter 10, just after Eig describes how Coretta settles into marriage, there is a section break — Eig then moves away from Coretta to discuss Martin’s rather difficult path through higher education, which included some moments of academic-borrowing and plagiarism.

There was something about that section break — that stark, physical divide between the description of Coretta’s shining potential and Martin’s academic struggles — that gave me a strange sense of foreboding. I felt it viscerally, so much so that I had to get up and walk around before returning to the book. Were Coretta’s talent and ambition going to be sidelined for Martin’s awkward educational accomplishments?

This is indeed what happened. Coretta would accept this sidelining as the civil rights movement grew in intensity and impact. She wanted to support a husband who felt the strain and danger of being Martin Luther King so intensely that it almost broke him several times. Coretta knew Martin needed her to be his wife. And even as a wife, she was still an activist, making appearances in her own right or in Martin’s stead. She remained a singer, giving fundraising concerts, alongside the likes of Belafonte, for the cause.

Still, she had wanted to do more for the movement, to play a bigger part. She felt called, too. But so often, the answer was: no.

Eig recounts a conversation between Coretta and Martin, just after the March on Washington. Martin was invited to the White House.

‘“I’d like to go,” said Coretta, who had spoken to President Kennedy on the phone but had never met him.

“Oh, you can’t go,” King told his wife.

“Well, I don’t see why I can’t go.”

He blamed it on protocol. Coretta wasn’t on the list of approved visitors.

“Well, alright then,” she said.’ (340)

In the course of their marriage, there were several such conversations.

Eig never wastes the opportunity to weave Coretta into the story, such that, by the end, King feels as much about Coretta as it does about Martin Luther King.

There are, of course, biographies about Coretta, although not as many as you might expect. I often think about the ways that biography itself is inherently a male genre because it tends to elevate the singular over the network, to glorify the public over the private. And, historically, men have usually occupied these public roles, whereas women have worked through whisper networks and behind the scenes while caring for the children at home. All too frequently, they remained out of the spotlight because stepping into it was too destructive or dangerous.

There are signs that this approach to popular biography is changing, that women’s hidden historic roles are being acknowledged, although even this effort comes with its own problems. I saw an example of this in Bradley Cooper’s latest film, Maestro, about Leonard Bernstein and his wife, the actress Felicia Montealegre. On the one hand, we sympathize with Felicia, whose star was rising. She steps back for Bernstein’s career, all the while nursing a private humiliation as her husband wrestles with his sexual attraction to men. She is the wounded wife.

But while acknowledging her sacrifices, Cooper leaves out an entire narrative about all that Felicia Montealeagre did, in fact, achieve. Even a quick jaunt through Wikipedia will tell you that Felicia did much more than Maestro lets on. Among other activities, she worked for the anti-war effort in the 1960s (for which she was arrested), supported the Black Panthers, and partnered with Amnesty International in Chile. In 1974, she published a report on the New York State parole system along with several co-authors, including…Coretta Scott King.

Genre determines content and constraints, as does the marketplace. A movie is only about two hours long, give or take. How much can you include? And what will your audience pay to see? A book can do more than a film, although genre and market exert their own influence in the world of publishing, of course. The publisher of King knows readers will pick up the book and pay for it because they come to it expecting a story about Martin Luther King, Jr. But I hope that at least some readers will leave the book, as I have, thinking about Coretta.

I have to congratulate Jonathan Eig for crafting a story that is simultaneously about one man and about the civil rights movement itself, with all its players, led by the exquisitely awe-inspiring and flawed human being that was Martin Luther King, Jr. He was the embodiment of a mood and a movement much larger than himself. At the dawn of rapidly expanding media coverage on television and in the newspapers, it seemed imperative for one person to incarnate the voices of thousands. But as Eig shows, you cannot tell the story of the one man without telling the story of all those who stood behind him — and, in this case, the story of the women. And of one woman, in particular.

So, on this MLK Day, I am thinking about Coretta. And about all the women who have not yet received all the attention they deserve, but who have always served as the beating heart in the fight for justice, peace, and human dignity.

As always, thanks for reading.

I’m in the process of reading the Eig book which as you say is terrific. Was also struck by the picture of Coretta he portrays. I hadn’t known much about her other than the wife and widow. I was dumbstruck by King keeping her from going to the White House with him. Heart breaking.

I appreciate waking up and having this article to read on this holiday. Thank you!