I write this letter having just recently returned from London. Thanks to the pandemic, this was the first time I’d been back to London in three years, and what a joy was. The sun shone in a dappled, autumnal way, and the streets were bustling, yet not so crowded with tourists. I went to exhibits, restaurants, and bookstores, but mostly I spent hours walking through the city, reminding myself of how London looks, smells, and sounds. I slipped back into my usual haunts with an ease that surprised even me.

For many years, I have felt quite at home in London. I often feel that the way Londoners see me more closely mirrors how I see myself. In London — and indeed, in the UK more generally — I am ‘an American.’ All I have to do is open my mouth, and the British believe they know something about who I am, at least in terms of nationality. And it is my nationality that makes them curious about me, however simplistic their assumptions might be. Thus, cab drivers eagerly ask me about American politics or the American experience of the pandemic; other Londoners ask me a slew of questions about everything from Netflix shows to the American reaction to the death of Queen Elizabeth. Of course, I can only offer them my perspective — but I appreciate that they treat me like a cultural ambassador for the nation in which I was born and raised.

Identity is such a pliable, flexible thing. You cross an ocean and suddenly you become someone slightly different, though still the same as you’ve always been. As I’ve grown older, I’ve become more aware of the ways in which, as a biracial person living in the States, I steel myself daily for a conversation about race that inevitably surfaces when I least expect it. I’ve often wondered whether the multiracialness of my own background gives Americans permission to talk about race in ways that they wouldn’t attempt with others: since childhood, I’ve consistently explained that not every Asian person in the States is a recent immigrant, that ‘American’ does not mean white; I’ve smiled patiently as well-meaning people scrutinized the features of my face while exclaiming “I couldn’t tell!” I’ve waited patiently as others spoke of me as ‘Asian-American,’ which is true yet doesn’t quite capture the whole truth, and seems unfair to those whose experience as Asians in America I cannot entirely represent. These questions and statements are rarely malicious; people are naturally curious, though sometimes that curiosity produces thoughtlessness and insensitivity.

Is my experience as an American an Asian one? Yes — because the Asian experience in America is a vast tapestry, just as it is for every other race and identity. Yet, Americans are often eager to categorize and box people in, to hyphenate identity as if the prefix and hyphen tells you anything about anybody at all.

I can’t help but feel that this focus on race as the fulcrum of identity has become more pointed in America in recent years. Perhaps because I was raised in California, perhaps because half my family hails from Hawaii — both highly diverse places — I have always thought of myself as American first and ethnically Chinese, German, Irish and anything else only second. Of course, California and Hawaii have their share of racism woes in part because of the diversity of their populations, and the same holds true of the UK. Still, London is proud of its diversity and it should be. I have never lived in a place with so many different skin tones and with so many different accents as in London.

I do not mean to suggest that somehow the UK is less racially focused than the US. British racism has a long history, indissociable from the empire; it’s a racism with a specific British edge, tinged with classism. As an American living in London, I have been shielded from this. I didn’t come up in the system: I didn’t attend British schools, I haven’t worked under a British employer. I am a writer and scholar and the UK boasts a culture that respects writing, scholarship, history, and intellectualism. But I also think I have been shielded because my own American voice precedes me. Most British people hear the accent and leave it at that. ‘She’s an American,’ they think. And indeed I am.

What I am saying is this: in the hierarchy of difference — a hierarchy that is shuffled and re-ordered whenever one visits a different culture of any kind — my status as ‘American’ rises to the top when I am in the UK. It is ‘Americanness’ that defines me to most British people I meet. They may still attempt to simplify the narrative, still search for patterns; this is only human nature. But how they do it feels more commensurate with my own sense of self. Of course, the British are still associating a ‘value’ with my Americanness — to me it just feels like that ‘value’ or that baggage is often a little closer to correct.

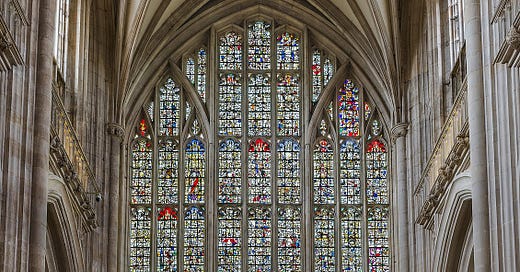

All of this was driven home for me several years ago at a conference in Winchester, a small city just a few hours travel outside London. Winchester boasts a beautiful cathedral, my favorite in all of Europe. On that visit, I signed up for a tour. As we were waiting to begin, a few of us were chatting. I don’t remember what I said, but one guide — a portly man, white and white-haired — perked up. “You’re an American,” he said. “You’ll want to see the American window, then.”

Within a few seconds this man and a fellow guide had whisked me over to a beautiful stained-glass window, explaining that it had been unveiled by Joseph P. Kennedy in 1938 as an American tribute to King George V, one of many contributions Americans had made to Winchester Cathedral over the years. Both guides gazed up at that window, beaming, then looked at me expectantly, waiting for me to beam in turn. And beam I certainly did, in part because the window was gorgeous, in part because I did want to see it, just as I wanted to hear all they had to tell me about its history and the American relationship to the cathedral.

But I was also beaming because they assumed I would care about Joseph P. Kennedy and the American window simply because I was American. Because just by listening to me for a few moments, these two elderly men, seemingly British through and through – emphasis on seemingly, for what do I know? – these two men had gotten a few things about me surprisingly right.

I enjoyed reading about London and race. Thank you very much for sharing. It is so complicated at times and sometimes can bring beautiful surprises. I enjoyed the ending. Thank you!

I routinely have the same experience crossing the Atlantic in the other direction, to North America: I open my mouth, they know I'm British, and that is the most defining element for strangers with whom I have everyday interactions.