Progress, progress: by the end of this week, Young Queens should move on to copyediting at Bloomsbury. After working on this book for years, I’m exhilarated and – I’ll admit it – relieved to finally be at this stage. And after several rounds of editing, everyone on the team agreed that we should salvage a tiny bit of Elizabeth Tudor’s story from the cutting room floor. This feels like a win! Still, Elizabeth is a full-grown woman by the time she appears in the narrative of Young Queens. So today I offer one more glimpse of the young girl before saying farewell to her for good…at least for this book.

Try to imagine Elizabeth Tudor at about eleven years old. Red hair, pale skin, long lovely fingers, probably a few freckles. We don’t have a picture of her at that age, but she must have looked something like this, only a couple years younger:

She was a curious, fiercely intelligent, and heartbreakingly vulnerable young girl who wanted nothing more than for someone to pay attention to her. She’d grown up under a domineering father, Henry VIII, who made her suffer for the supposed crimes of her mother, Anne Boleyn. She was considered an illegitimate child. As third in the line of succession, she had little hope of inheriting the English crown. She had few friends among her peers, and rarely saw her father.

But, oh, how Elizabeth wanted to be seen – really seen, for all her gifts and abilities. You can see all that desperate wishing in a little project Elizabeth conceived in December of 1544, a gift for her stepmother Katherine Parr, the sixth and final wife of Henry VIII.

Elizabeth and Katherine were close. Royal children didn’t usually live with their parents, but Elizabeth had Katherine had lived together for several months during 1544. During that time, Katherine had paid a lot of attention to Elizabeth, sewing, reading, and writing with her. Having never really known her own mother or any of her other stepmothers, Elizabeth grew very fond of Katherine.

So that December, she decided to make Katherine a New Year’s gift. What she ended up producing was a kind of tour de force, showing off all her talents. Elizabeth translated an epic-length French poem (1400 verses!) into English prose, penning the entire manuscript herself in beautiful, flowing handwriting. It’s quite a feat, though you can still tell that it’s the work of a child. Sure, the translation is astounding. But from the handwriting, it’s clear she had to race a little at the end. Maybe she bit off a bit more than she could chew.

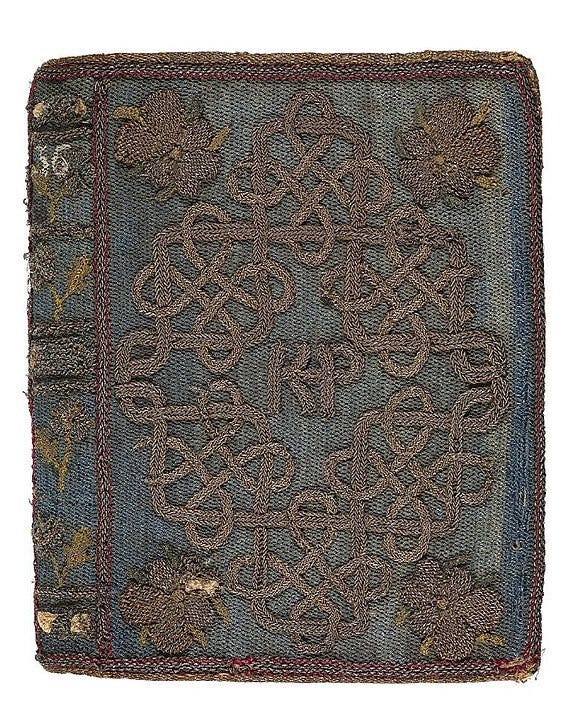

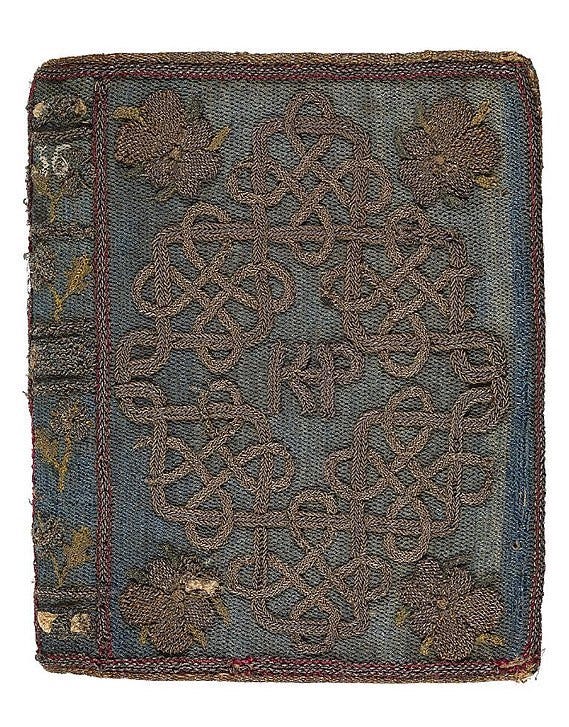

There was even more to this little gift: Elizabeth decided also to embroider her own book cover. It was like an arts and crafts project, except that the cover was quite a nifty piece of handiwork. With her needle, Elizabeth whipped a sheet of canvas with tiny blue-silk stitches. In the corners she sewed little yellow and purple flowers. There were knots of gold braid woven all over the front and, just at the center, Elizabeth embroidered her stepmother’s initials: “KP.”

When I first saw Elizabeth’s little book years ago, the cover amazed me as much as the poem. I don’t sew or knit myself, so I was astonished that a young girl could embroider so well.

But during the pandemic, I learned how quickly a child could in fact master these skills. While we all hunkered down, my own eleven-year-old daughter began to crochet for hours a day. I had no idea you could crochet earrings, but now my jewelry box is full of them. Our house overflows with doilies, coasters, granny squares, crocheted slippers, and blankets. My son even got a little crocheted figurine that looks remarkably like “Wanda” from Marvel’s “Wanda Vision.” My daughter has moved on to sweaters and skirts and next up, she tells me, is a pair of crocheted pants.

How did my daughter learn to crochet? YouTube. How did Elizabeth Tudor learn to embroider? Probably Katherine Parr taught her a stitch or two. Both girls wanted to make pleasing gifts – and both wanted to show the grownups what they could do.

There is something so earnest and endearing about Elizabeth’s little book, so ingenious and yet so childlike. She used every skill in her toolbox, needles and pens, silk thread and paper. She wanted to show she could make something pretty and that she could use her mind. She likely pricked her finger more than once. In the final days, with the New Year approaching, she probably stayed up late, working by candlelight, straining her eyes. Clearly, she wanted to please Katherine Parr, but I also suspect she hoped her father would see the book and approve of her, too.

I can’t help but see in her book a kind of defiant act and a cry for attention, all in one. As if she were saying, “Look at me! Look what I can do! I may be third in line to the throne, I may be illegitimately and a girl, but my fingers are nimble, and my mind is fierce.” Elizabeth poured her entire self into that little book. Not unlike my own daughter – the third of my children – carving out her place in the family with that crochet hook.

And, in the end, I think Elizabeth knew how well she had done.

The original book still lives in the Bodleian library at Oxford where the librarians serve as strict gatekeepers (hardly anyone gets to touch it!). Mercifully, they’ve digitized it, which is almost – almost – as good as seeing it in person. You can get a closer peek at the cover and a page from Elizabeth’s manuscript here:

https://treasures.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/treasures/princess-later-queen-elizabeth/

By pure coincidence, I found this Instagram reel in my feed just this morning. If you’re on Instagram, have a look if you want to see embroidery in action.

https://www.instagram.com/reel/CgbrPL-FfVw/?igshid=MDJmNzVkMjY=

Happy August to all!