Kamala Harris has faced plenty of gender-based insults over the years. One of my personal favorites showed up in 2021, when Fox News dubbed her the “Crochet Czar.” That year, Harris paid a well-publicized visit to the woman-owned and Black-owned Fibre Space, a shop dedicated to the fiber arts in Alexandria, VA. I live near Fibre Space, and it is one of my favorite shops. The yarns are beautiful, clouds of cotton, silk, and wool. Harris, who has been crocheting since childhood, also admired the store. But besides having a personal attachment to yarn, Harris visited the shop mostly to learn about the experiences of female small business-owners.

Fox News pounced. Calling her the “Crochet Czar” was clearly meant to belittle Harris and all wool-loving women, conjuring up the worst sexist and ageist stereotypes associated with those who love the fiber arts – stereotypes that also place women in the realm of domesticity and men in the public sphere.1 The name-calling was pointedly gendered: Fox news implied that Harris wasn’t a real politician. No, she only cared about girly, frilly, wooly things.

As both a historian interested in gender and politics and a lover of yarn myself, I object.The insult, of course, is non-sensical. But the very concept of a “Crochet Czar” has made me think a little more about the intertwining of women’s craftwork and politics.

Offhand, I can think of several historical instances when women wielding needles have made themselves political. Catherine of Aragon, for instance, who continued to sew Henry VIII’s shirts well after he demanded a divorce: this was visible resistance to the divorce, a deliberate show of her loyalty to her husband. Or how about the women who sewed the Phrygian caps, the head gear of the common people, during the French Revolution? Or, in the States, Betsy Ross and the flag? Moving to our modern times, there is yarn bombing – a form of graffiti in which women, and indeed people of all genders, wrap everything from stop signs to buildings to bridges in intricate crochet and knitting. Yarn bombing is eminently peaceful – there are, in fact, no actual bombs. It is visually arresting. And sometimes, it is most definitely political.

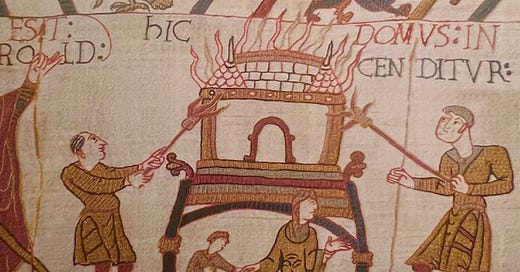

Recently, I had the opportunity to look at a much older instance in which fiber and needlework was put to political use. Last month, while traveling in Normandy, I had the chance to go to Bayeux to see the Bayeux Tapestry – something I’ve wanted to do for decades. A thousand years ago, women wielding needles and wool produced one of the most long-lived and powerful examples of political propaganda ever made. The story the tapestry tells has become a pillar of Western political history: it is the story of the Norman Conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066.

The Bayeux Tapestry is not, in fact, what might properly be called tapestry. It is a piece of embroidery, a long strip of linen measuring over 220 feet.2 On that stretch of fabric, needleworkers sewed an illustrated account of the Norman Conquest, featuring a clear plot line with well-developed characters and exciting battle scenes. The Tapestry is like a medieval graphic novel. It’s a great story, told mostly in pictures, for an audience who couldn’t read.

In a few sentences, here is that story: The ailing Anglo-Saxon king, Edward the Confessor, names his cousin, Duke William of Normandy, as his heir. Edward sends a faithful messenger, Harold Godwinson, across the sea to convey that information to William. The journey is difficult; Harold suffers but carries on.

In Normandy, Harold conveys the message to William, and pledges an oath of loyalty to him. But once back in England, Harold breaks his oath and claims the throne for himself! Learning of Harold’s treachery, Duke William musters an army of Normans, invades England, kills Harold in the Battle of Hastings, and claims his throne. Forever after, he is known as “William the Conqueror.”

The version of the story recounted on the Bayeux Tapestry is remarkably secular – there are few references to God or even religion. It’s a political story. It’s also propagandistic, a version of history that may have indulged in a little revisionism. The Tapestry gives the Norman Duke William good reason to wield the sword against the Anglo-Saxons: it’s because Harold betrayed him. But are we sure that Edward the Confessor really named William his heir? As one of my astute traveling companions noted, if William was in fact the legitimate heir to the English throne, shouldn’t he be known as “William the Legitimate” instead of the “Conqueror”? Perhaps those who designed the Tapestry had a certain agenda in mind. Moreover, everyone loves a hero, and “William the Conqueror” certainly has a more heroic ring than, say, “William the Valid.”3 [3]

The Bayeux Tapestry is also unapologetically masculine, as one might expect of a medieval story about war. There are women depicted in the Tapestry, but they are few and far between and mostly unidentified. As Philippa Gregory has pointed out in her recent book, Normal Women, while there are 8 female figures who show up in the Tapestry, there are 93 penises. Five of those penises appear on human men, but most belong to the war horses. Even so, the size of the horse genitalia tends to correspond to the importance of the men who own the horses. William’s noble steed, for instance, is fabulously well endowed. Harold, the antagonist, mounts a horse who proves to be somewhat punier. You get the idea.

Of course, women were present at the Conquest in all its brutality. In perhaps the most haunting and moving scene of the Tapestry, there is a depiction of an unnamed Anglo-Saxon woman holding the hand of a young child as they try to flee the Norman forces who were pillaging, burning and, no doubt, raping.

The inclusion of this particular image raises questions for me. The Tapestry is supposed to commemorate the Conquest -- by including this unnamed woman and child, is the Tapestry celebrating the Norman destruction of English people and villages? Or is this a nod, however slight, to the terrible price of war?

We cannot know, in part because we don’t know who commissioned the Tapestry or who designed it. Most scholars believe Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Duke William’s half-brother, commissioned it, but some have suggested that William’s wife, Matilda, was responsible, or perhaps Queen Edith, the widow of Edward the Confessor. Unfortunately, there is no hard evidence to prove any of these possibilities.

If we can’t be certain who ordered the tapestry, we are pretty sure who made it: a team of female embroiderers. There is good reason to believe that the Tapestry was created in England shortly after the Conquest, rather than back in Normandy. And in 11th-century England, embroiderers were usually women.

These women may have been nuns. But possibly they were professional craftswomen working in a workshop dedicated to embroidery. From the evidence of the Tapestry itself – the stitching, the layout, the sheer length of the linen pieces – the work was produced by several teams, each collaborating on large swaths of linen pinned to wooden frames. The embroidery was highly artful, requiring several types of complicated stitches then in vogue. The intricate design required visual imagination as well as precise measurements. The placement of the images had to be coordinated before the linen pieces were stitched together. Given the complexity of the entire piece, it seems possible that a supervisor or manager – perhaps a woman herself – orchestrated the work among the teams.4

I would also venture that a woman must have been involved in the artistic design of the Tapestry. After all, if only women embroidered at the time, the design team would have had to consult a woman to know what was possible to do with a needle and thread.

I imagine these needlewomen showing up to their work in the morning, bending their heads over the linen and the frames. I imagine the manager checking on the teams, reminding them of deadlines, nodding in approval, perhaps demanding a do-over. I imagine the women chuckling over all those well-endowed horses.

Then again, I can also imagine the soberness of the work. These were Anglo-Saxon women making a piece of art that celebrated the Normans, their colonizers. I can imagine the grief with which a needlewoman might have pulled her thread to make that image of the fleeing mother and child. Perhaps that English needlewoman knew someone whose life had been destroyed by the marauding Normans. Maybe her own life had been radically changed. Perhaps the designers knew this. Perhaps including that painful image of a woman and child fleeing was, in a way, a form of political resistance.

What none of those needlewomen could have imagined is that their handiwork would endure for generations. The visual story they stitched together was so powerful that it inspired would-be conquerors almost a thousand years later.

Napoleon saw himself in William the Conqueror and ordered the Tapestry to be displayed in Paris to justify his plans to invade Great Britian. Over a hundred years later, the Nazis wanted the Tapestry too. They moved it to the Louvre and had plans to send it to Germany, where the narrative of the Conquest would have been appropriated to promote Aryan supremacy. Ultimately, the Nazis’s plans were thwarted by British spies and the French Resistance.

What is the message in all this? On the one hand, there is something twisted about the way that women’s work with needle and thread has been used and exploited for the sake of masculine narratives of politics, war, colonization, and domination. Most women in 1066 would have learned to embroider for the sake of livelihood, art, or sheer industriousness -- they probably didn’t see their needles and thread as instruments of war.

But the Bayeux Tapestry also shows us that women’s traditional handiwork has always had the potential to be politicized – and that stories of male victory and virility have often depended on women’s work for their power and their reach. In a way, you could argue that women’s role in the weaving of such propagandistic narratives made them complicit in these stories, even if their participation was compelled. Then again, in that work, perhaps there are hidden moments of resistance that we might find if we look closely enough. No matter the case, through their handiwork, women became political actors – even at times when women didn’t have a political voice.

This was true for the Bayeux Tapestry, for Catherine of Aragon, for the makers of the French Revolution’s Phrygian caps. Even now, after women have acquired a political voice, yarn bombers have found a clever way to turn the seemingly staid and domestic into vibrant political action.

As for Fibre Space? I’m happy to say that after Fox News tried to mock the so-called “Crochet Czar,” the shop in Alexandria, VA readily jumped into the political fray. Fibre Space made a beautifully designed pin with a picture of Harris and the words “Crochet Czar” artfully rendered underneath.

You can still purchase it. Maybe you want to pin it on your knitting bag. And just like that, a crochet hook, a knitting needle, a skein of yarn become symbols of women’s political engagement, ascendance, and resistance.

No different from what they’ve always been.

Never mind that Fibre Space attracts many men among its clientele, and that increasingly, men are powerful influencers and advocates in the world of fiber arts. The stereotypes associated with crocheting and knitting are still gendered female.

In a proper tapestry, woven on a loom, the images are woven as part and parcel of the fabric, whereas in embroidery, the images are sewn into the fabric.

Although, like in any epic, sometimes the antagonists are the most compelling. Consider, for example, Darth Vader. The designers of the Bayeux Tapestry seem to have been quite intrigued by bad guy Harold Godwinson because half the Tapestry is dedicated to him.

https://www.historyextra.com/period/norman/bayeux-tapestry-where-make-how-long-who-when-stitch-penises-visit/

The Bayeux Tapestry, I saw it in France many years ago and realised that it was embroidered propaganda. It is a mixture of triumphal William worship and a successful attempt to legitimise his invasion. Your article is so interesting and well written . It takes real talent to make embroidery and crochet exciting, to me at any rate. We talk of the Normans and the Anglo Saxons though as if they were two new forces in opposition. Considering family roots, the Scandinavians had already seized the English throne by force centuries previous to the Conquest and probably the best bit of early propaganda concerned Canute and his marvellous magnanimity. History is always seen through the eyes of others and there are many versions of the same event to be read, depending upon who was watching and their bias. So, the tapestry, wholly Norman biased giving legitimacy to a history changing event about which we still have no real idea of who was the goodie and who was the baddie.

This was FANTASTIC! I absolutely loved the voiceover, it added just a wonderfully personal touch to this and better understanding your tone only elevated you’re already incredible writing! Thank you for taking the time to add your voice—I know that comes with another layer of vulnerability when putting your words out into the world, and I’m sending love your way for whatever feelings/nerves came up when hitting publish.

In all of the time I’ve spent pondering this phenomenal work of art, I’ve never once stopped to empathize with the heaviness of telling the story of your own country’s colonization, of the death of your fellow countrymen. Thank you for sharing that with us, I know I’ll be thinking on it for some time.