Give the Queen a Pair of Gloves

Some Gift Giving Advice if You’re a Courtier in Elizabethan England

If you’re enjoying this free newsletter, please click on the red “share” button at the end to send it to a friend. Clicking on the “like” button also helps get my writing in front of more eyes. And thank you for reading!

Imagine you’re a courtier in late 16th-century England. It’s December and New Year’s Day is approaching fast. In Tudor England, New Year’s Day is the gift-giving holiday, rather than Christmas. And no doubt, you’ve been planning your gifts for months since, after all, this is the 16th century and you can’t just go to the mall or pop online. Of course, if you’re an English courtier, the most important gift you have to choose is the one for Queen Elizabeth I herself. And what is a plain old courtier supposed to give Her Majesty, the woman who has everything?

Why, a pair of fine kid gloves, of course! Preferably bleached white with jewels for buttons or embroidered with gold thread. What more could a queen want? And everyone knew Queen Elizabeth loved a pair of fine leather gloves. She also loved silk ones and velvet ones, and really any and all kinds. We still have the gloves she wore on her coronation in 1559 when she was 26 years old. You can compare them to the ones that Elizabeth II wore at her coronation about 400 years later in the picture below.

Elizabeth I (the 16th-century queen) was notoriously vain about her hands. She seems to have been aware of their beauty from the time she was a young girl. Almost every portrait of her, from the age of 13 on, features her hands. Sometimes in those pictures they are covered in rings (which she also liked). Sometimes they are bare, especially as she got older. Her ringless fingers signified that she had never married. But Elizabeth was also proud of her hands even when unadorned. Slender, pale, with long thin fingers, they were ornaments in themselves.

If you were a foreign dignitary visiting Elizabeth’s court, and she deigned to remove her glove and allow you to kiss her hand, you knew the visit was off to a good start.

In 1562, only a few years into her reign, the young Queen Elizabeth fell deathly ill of small pox. Her doctors and privy council feared for her life. Elizabeth was unmarried and there was no clear line of succession — what would become of England if Elizabeth died?

This was a political crisis of enormous proportions. But as one doctor noted, as concerned as Elizabeth might have been for her kingdom, she also worried the pox pustules would scar her hands. She seems to have cared more about what happened to her hands than to her face.

Elizabeth’s life was spared. The skin on her face may have scarred, but we don’t know for sure. Some scholars suspect that her use of thick white makeup was a way to cover the pockmarks. But her hands, it seems, were unscathed.

Perhaps, as her reign went on, Elizabeth kept drawing attention to the beauty of her hands in part to distract from any scarring on her face. Or, as she aged, from any wrinkles or spots, the marks of time. Beauty wasn’t only about vanity for Elizabeth. Her somewhat infamous vanity may have been pragmatic: Elizabeth recognized that for a queen, style, beauty and aesthetics conveyed power.1 A master brander, Elizabeth would transform her hands into a trademark.

Hands were symbols of power and mastery. The teenaged Elizabeth holding a book, one that looks much like a Protestant prayer book? Clearly she is studious and dedicated to her faith.

The middle-aged Elizabeth holding a sieve the symbol of the Roman Vestal Virgin Tuccia? Clearly Elizabeth is master of her own body, her virginity preserved by choice, the province of no man.

Or the older Queen Elizabeth caressing a globe with one hand and holding a fan in the other after England defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588? Elizabeth is master of the universe. She holds the world in her hand.

Her hands were instruments of war, of peace, and also of healing. Like other English monarchs, Elizabeth believed her hands possessed the power of the Royal Touch, the ability to cure skin diseases like scrofula. On special feast days, Elizabeth would go out among her people, laying her hands upon the sick. Her hands became God’s instruments, imparting medical miracles.

They were delicate yet strong; beautiful yet commanding; human yet divine; feminine yet kingly. Elizabeth’s hands were a mark of her particular, almost contradictory power as a sovereign queen. May I suggest that they came close to being a female phallic symbol? Or a sign of female virility?

Uber-masculine kings like Henry VIII of England or Philip II of Spain liked to show off their codpieces. These were decorative pouches made of silk, leather, velvet, or even metal. They were attached to men’s breeches and covered their genitals. They could also be…ahem…augmented in size according to the wearer’s preference. Codpieces were all the rage among elite European men in early 16th century.

Elizabeth, of course, could not sport anything like a codpiece. But she could flaunt her porcelain hands in portraits and in person. She could turn the removal of a glove into an act of both dramatic suspense and seduction, gracefully pulling at the tips, stripping away silk and soft leather to reveal first her slender wrist, followed by those supple, sinuous, and sensual fingers. The glove laid aside, she would offer you those fingers, to kiss. This was a dance between queen and dignitary. This was Elizabeth’s way of saying, “See? I had you at hello.”

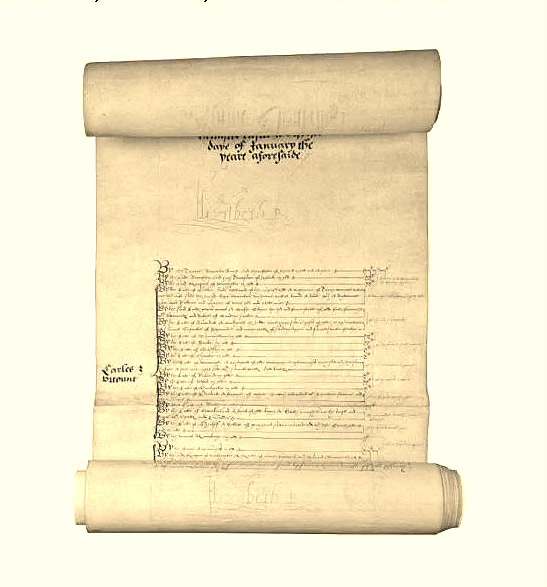

So, English courtiers in need of a royal gift would have done well to present the Queen with a new pair of gloves. Judging from the New Year’s Gift Roll of 1601 - the official record of who gave what to the queen — dozens of people had this exact idea. A pair of gloves was certainly a safe gift, one the queen was sure to like. A show of appreciation for her finest feature and an acknowledgment of her power.

I hope you have a wonderful holiday season. See you again in 2025.

When she was younger, and still held out marriage as a possibility, her beauty also conveyed the promise of fertility. As she aged, Elizabeth’s fertility was no longer centered. But scholars have noted that her portraits from middle age on usually made her look much younger than she actually was.

Fascinating analysis! I really hope you’re working on another book! Loved Young Queens and so enjoy your newsletter.

This essay was such fun! My eyes were often drawn to the hands in these portraits - I love how you interpret them!