Don’t you just love it when a 500-year-old queen (one who happens to be a major figure in the book you just wrote) makes headlines? The Washington Post, Smithsonian Magazine, CNN, and dozens of other outlets all carried the story: after five centuries, cryptologists have finally cracked the code that Mary, Queen of Scots used to write the French ambassador while she was imprisoned in England during the 1570s and 1580s. In case you don’t know the context, I will sum it up quickly here. Apologies for the lack of complexity – for the sake of brevity in what is nonetheless a long post, I offer only the sparest of outlines.

In the summer of 1568, Mary, Queen of Scots, then twenty-five years old, fled Scotland to England, having been ousted from the Scottish throne by Scottish Protestant rebels. Once in England, she asked Queen Elizabeth I for protection and for help in recovering her crown. Elizabeth I, however, was suspicious of Mary’s intentions: she knew Mary had coveted the English throne for years. When Mary suddenly showed up in England, Elizabeth worried that English rebels would flock to the beautiful and charismatic Scottish queen. You should know that there are a lot of religious questions behind this issue: the English Elizabeth was Protestant and Mary was Catholic. I won’t go into that here. In short, it’s enough to know that Mary’s arrival made Elizabeth, who was quite an insecure queen for good reason, extremely nervous.

Elizabeth’s solution to this problem was to keep Mary under house arrest in England for over twenty years. Eventually, Queen Elizabeth’s advisors convinced her that Mary was indeed plotting against her. Mary was tried and convicted. On February 7, 1587, she was beheaded at Fotheringhay Castle.

Got that? This is a well-known story to those familiar with Tudor history, and popular culture has long been enamored of it. Schiller wrote a play in the 1800, Donizetti made an opera from it, the Romantics penned poems and painted paintings, writers churned out biographies, directors shot movies, and on and on. And yet, we never seem to tire of the story. But is there more to say about it, or to know? (Yes, I say, having just written a book about the young Mary. But let’s turn to these new letters).

The recently decoded letters date from 1578-1584. Most are addressed to Michel de Castelnau, sieur de Mauvissière, the French ambassador in England, who communicated with the Scottish queen through secret channels. Mary had every reason to hope the French would come to her aid: she had been raised in France and was once married to the teenage French king. She was the niece and cousin powerful French noblemen. Though she reigned in Scotland, she considered France her home. But for political reasons, the French were rather tepid towards Mary. She wrote letter after letter pleading for their help, reminding them that she was family, sending along bits of information she’d picked up, as if to win French assistance by plying English political secrets. The newly decoded letters are just some of the hundreds that she sent through secret channels. The utmost secrecy was essential. Mary was, after all, a prisoner of the English queen, and English spies were everywhere.

The decoded letters were not exactly new discoveries. In fact, they were hiding in plain sight. Over the years, they had somehow been bound together with other letters housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) in Paris. Since the rest of the letters in those bound volumes mostly dated from the 1520s and 1530s and concerned Italian affairs, and since the enciphered letters had no other markings to identify them, no one realized what they were. These BnF letter collections have been digitized, their contents easily viewed online. I have handled them myself on research trips to Paris. But like countless other researchers, I simply paged through the enciphered letters, wishing I could read them, yet moving quickly on. I had no idea that I was touching letters that Mary, Queen of Scots had herself once handled.

How often do we hear of such discoveries? A ‘lost’ medieval manuscript, for instance, found on a university library shelf by a graduate student? A letter by a famous writer gathering dust in an attic, or a masterpiece by a revered artist, moldering in a basement? Such discoveries do not happen every day, but they seem to occur on a regular basis. And then everything we thought we knew about that writer, that artist – that queen – shifts just a little. This is what I love about history. The book is never closed. There is always something new to tweak the story, something more to learn.

In Mary’s case, the latest decryptions will likely reveal a trove of new details once historians get their hands on them. But just as fascinating to me as the letters are the men who decoded them. They are not professional historians, but rather amateur cryptologists. ‘Amateur’ in the classic sense: although they are not salaried decoders, their passion for cryptology is boundless, and has led to years of deep and dedicated labor. ‘Amateur,’ perhaps, but hardly ‘inexpert.’ Quite the opposite, in fact.

Their endeavor was as collaborative as it was international. Dr. George Lasry, a computer scientist working in tech, received his PhD from the University of Kassel and has worked on German diplomatic codes from World War I and World War II, along with papal ciphers from the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. Norbert Bierman, also trained in Germany, is a professional pianist who decodes for fun and who has published papers on historical ciphers. Last, but not least, is Satoshi Tomokiyo, who studied astrophysics in college, works for a patent firm in Tokyo, and “devotes his private hours to research of historical cryptography,” all while managing a website devoted to cipher and cryptology. Together they toiled over years, and have just published their findings in an article, over 100 pages long, in the latest issue of the journal Cryptologia.

What a team.

I like to imagine these intrepid cryptologists poring over the BnF’s digitized letters, studying printouts, sending each other excited emails, straining together through periods of bafflement, slowly putting the pieces together. I imagine the shock and disbelief when they realized they were decoding letters by the legendary Queen of Scots. How awe inspiring it must have been for them to know they were responsible for bringing the world a fuller portrait of her activities, thoughts, and feelings, of her voice. Maybe it was even a little frightening. No doubt, it was thrilling.

And there is another idea that enthralls me: I imagine Mary in captivity, carefully penning the cipher. Then, she seals the letter in a lengthy series of turns and folds. The process was known as ‘letter-locking’ and its purpose was to fold the letter in a pattern that would seal the sensitive contents on the inside, while a piece of the letter itself was used to close and ‘lock’ it. The letter could only be opened by breaking the paper lock. If the person receiving the letter saw the lock had been torn, they would know the letter had been tampered with.

Mary ‘locked’ the last letter she ever wrote in this way. Might she have done something similar with her enciphered letters to Mauvissière?

Using her secret channels, Mary then sent her letters to the French ambassador. Most of them probably made it into Mauvissière’s hands safely, although others were certainly picked up by English spies. Eventually, hundreds of years later, they landed in the BnF, filed away as “items in cipher.’ And there they remained, impenetrable until their digital versions landed under the eyes of two men from Germany and one from Japan.

Spies! Secret codes! Mysterious messengers! A fearless team of cryptologists! And the pathos of a queen desperately seeking her freedom and her lost crown, to no avail.

Thousands of miles separated Lasry, Bierman, and Tomokiyo from the encrypted letters at the BnF; hundreds of years separated them from the woman who wrote them. Mary wrote her letters with quill and ink; modern technology and methods enabled their re-discovery but, as the cryptologists point out, they were limited to what was available in the BnF’s electronic holdings. Which raises an important point: there must be other unknown letters — by Mary and others — in those archives. What treasures await discovery in libraries around the world?

In their article, Lasry, Bierman, and Tomokiyo mostly focus on their methods. They did not publish the letters in full, although they hope to collaborate with scholars to produce an annotated edition. However, they did reproduce a few snippets, and I can’t help but appreciate this passage, in which Mary hopes the powerful Queen Mother of France, Catherine de’ Medici, would help her:

“I thank you for the good advice,” Mary wrote to the ambassador, “to ask the Queen Mother, if she proceeds with her trip to Calais, to send a gentleman here on her behalf to help me in my requests for freedom. Please do this good service for me, and apologize to the Queen Mother for not writing to her personally, for I do not dare send anything by this channel unless it is enciphered, and if I use the usual route, it would not fail to be discovered.”1

She had sought similar favors in the past and would continue to ask for help over the coming years. But although the French did send envoys to England, Mary was not their priority. The Queen of Scots would spend the rest of her days a prisoner.

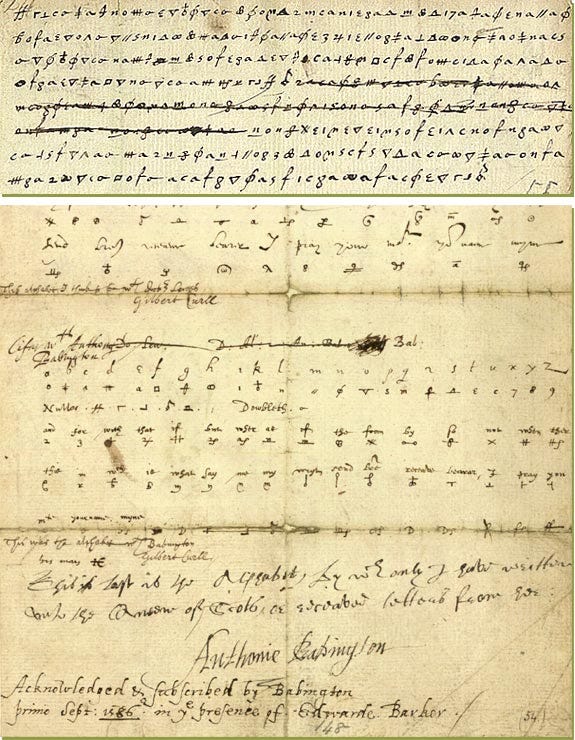

In the end, although she hoped cipher could free her, it was cipher that condemned Mary to the scaffold: Elizabeth I’s chief spy, Francis Walsingham, hired a cryptologist to forge an enciphered postscript in a letter Mary wrote to the Catholic Anthony Babington — the postscript seemed to implicate her in Babington’s plot to bring Queen Elizabeth down.

You can listen to a delightful conversation between the historian Dr. Suzannah Lipscomb and Dr. George Lasry, on “Not Just the Tudors,” which, by the way, is one of the best history podcasts out there. And you can read the article by Lasry, Bierman, and Tomokiyo here. The article is open access, as it should be. Free and accessible — isn’t that the best kind of scholarship? As our cryptologists have proven, history belongs to everyone, and sometimes amateurs make the best discoveries.

Countdown! 77 days until the launch of Young Queens: Three Renaissance Women and the Price of Power in the UK (May 11); 173 days until launch in the US (August 15). You can pre-order the Bloomsbury edition (UK) here, and Farrar, Straus and Giroux edition here.

This is my translation from the French given in George Lasry, Norbert Biermann & Satoshi Tomokiyo (2023), “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s lost letters from 1578-1584,” Cryptologia, DOI: 10.1080/01611194.2022.2160677 ; the authors also offer a translation in English.

This is really captivating! This gives me a good illustration of why history can be so captivating! Love the video! And how exciting to know that your book is coming out counting the days!