Olympe de Gouges: A Radical Feminist, Executed by Guillotine during the French Revolution

Lately, I've been thinking a lot about her.

Hello to new subscribers! A gentle reminder that if you like what you read, please consider clicking the heart on the top or bottom of this newsletter. You can also click the “share” button to send it to a friend. We’re all at the mercy of algorithms, but a simple click really does help get my writing in front of more eyes. Thank you for your support!

On November 3, 1793, Olympe de Gouges stood on the scaffold in the Place de la Révolution in Paris. Below her the crowds pressed close, straining for a better view. Behind her stood the guillotine, the instrument of state-sponsored violence. A basket sat at the base of the machine, ready to collect the head — her head. Parked next to the scaffold, a lone cart waited to haul her corpse away.

Across the square, in full view of the crowds, stood a giant Statue of Liberty, created by the Revolutionary artist Jacques-Louis David. The statue stood for freedom; Lady Liberty was the face of the new Republic. The guillotine was the Republic’s weapon, the means to ensure that freedom. Wasn’t it?

Olympe de Gouges was forty-five years old, although like many actresses and other fashionable French women of her time, she tended to fudge her age a little. Even with her life on the line, she could not be compelled to admit her true age. At her trial a day earlier - a sham of a process, in which she had been denied a lawyer and was told that she could defend herself because she was accustomed to speaking out in public - Olympe told the prosecutor that she was 38.

Accused and condemned for sedition against the French Republic, she was sentenced to death. Around 3 pm on November 3, she stepped into a cart and made the hour-long trip to the scaffold. She wore only a plain white shift, ratty and dirty after her weeks in prison. It was cold and damp that day. Her hands were pinned behind her.

To put this in historical context, let me quickly give you a few dates: by 1793, the French Revolution had been going on for about four years, since the summer of 1789. The state had begun executing political prisoners by guillotine in the summer of 1792. The French king, Louis XVI, had died on the scaffold in January 1793, and Marie Antoinette, his wife, had been executed in October 1793, just weeks before Olympe was sent to the scaffold.

By the fall of 1793, the French Revolution had entered the brutal phase that came to be known as The Terror. It would last until the summer of 1794. During that time, anyone, regardless of class or political affiliation, could be arrested, tried, and sentenced to death for “anti-Revolutionary thinking.” Nothing needed to be proved; you could land in prison for the mere suspicion of anti-Revolutionary thinking. No one was safe. Fear walked the streets and vigilantism reigned.

Olympe de Gouges was not an aristocrat, although she claimed to be the illegitimate child of a marquis (and many historians believe this to be true). Olympe’s legal father was a butcher. Her mother had been born into a comfortable middle-class family. Raised in the south of France, in the town of Montauban, Olympe was married to a merchant at 17 and became a mother soon afterward. The marriage was unhappy, although we don’t know the exact circumstances. Olympe herself would say later that her parents married her off despite her wishes.

She did not remain married for long. Olympe was widowed by the age of 19, although at least one scholar, John Cole, has speculated that Olympe might have run away from her marriage before her husband’s death. It is certainly possible.1

Then, the young widow made a decision that would change everything. After her husband’s death, she chose not to marry again. Instead, with her baby in tow, she ran off to Paris, changed her name (from Marie Gouze to Olympe de Gouges), took lovers to fund her lifestyle, immersed herself in the salons and theaters of sophisticated Paris, became a playwright and actress, and eventually, a political activist.2

In other words, she became something of a self-made woman. All this, in pre-Revolutionary France.

For a woman of her time, she held extraordinary ideas. She possessed a keen sense of justice and became an abolitionist, protesting the slavery that fueled the French sugar colonies in the Caribbean and poured money back into France.3

One of her earliest published works, a play called Zamore et Mizra (1784), told the story from the point of view of the enslaved protagonists rather than of the enslavers. This was the first play in France ever to do so. When Olympe finally succeeded in getting the Comédie française to stage the play in 1789, colonists and their supporters filled the seats of the theater and broke up the performance with jeering and howling.

As she always did, Olympe de Gouges simply carried on.

Radical in her thinking about race, she was also a radical feminist. Radical, I should say, for her time period if not ours, although we seem to be sliding backwards in many arenas, including women’s rights.

Olympe’s feminist awakening probably began during her difficult marriage. Then again, she may have felt certain stirrings earlier when, as a child, she saw how the marquis she presumed to be her father treated her mother. Like her English contemporary Mary Wollstonecraft, Olympe saw marriage as a kind of prison for women. She believed that women could lead autonomous lives, and that they should enjoy full civic rights equal to those of men.

Despite her thoughts about women and slavery, she was a political moderate. She embraced the Revolution, but never its violent extremes. She considered herself a patriot. And like many revolutionaries of her time, she believed that the execution of the king would lead to spiraling and unmitigated violence.4 In this, Olympe was prophetic.

But for a few years, before 1793, Olympe de Gouges dreamed alongside her fellow revolutionaries. Among other things, she believed the Revolution should carve out a space for women. The revolutionaries were building a new world. Why not take the opportunity to include women as full and equal civic partners?

Having abolished aristocratic titles, Revolutionary France called Frenchmen “citoyen” - citizen. Olympe believed that women should be citoyennes in every sense of the word.

That is how she signed many of her pamphlets and public letters: Olympe de Gouges, citoyenne.

Olympe de Gouges was a prolific writer. As the Revolution gained traction, she turned to writing pamphlets, placards, and posters. Pamphlets were like the social media of the 18th century, and Olympe did not hold back. Her writing was brazen, lively, often funny, and caustic. If she didn’t like you, she let you know (as Robespierre found out).

She was not an elegant writer, which may be why her writing was so often dismissed, both in her own time and in ours, at least until recently. But she was a brave thinker and a philosophical one. Today, she is known mostly among philosophers but, trust me - had Olympe lived in the 21st century, she would have been all over every social media channel. She wanted to speak to the people. She would have loved Substack, but also TikTok. She would have bravely stayed on X, despite the trolls. She faced her own trolls in the 18th century, but Olympe had a thick skin and always seemed to dive right back in.

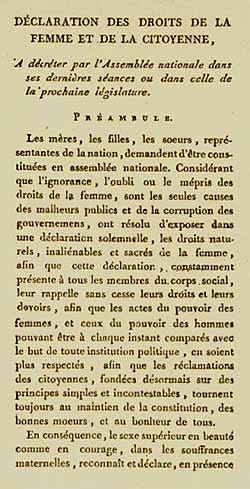

In the summer of 1791, Olympe published a short pamphlet, a manifesto called The Declaration of the Rights of Women. Today, that manifest is considered her most famous work, but the pamphlet doesn’t seem to have been widely read in 1791.5 That summer, a new French Constitution was about to be unveiled. Olympe made the case that women should be explicitly included, that women deserved equal civic rights in a representative government, including the right to hold public office and the right to vote.

There are 17 articles in the Declaration. You can read the full text in English online, but I’ll reproduce some of my favorites here:

Article 1: Woman is born free and remains equal to man in her rights. Social distinctions should be based only on the common good.

Article 2: The purpose of any political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of woman and man; these rights are liberty, property, security, and, above all, resistance to oppression.

Article 6: The law should be the expression of the general will; all citizens, female and male, should participate in person or through their representatives in its formation; it should be the same for all: female and male citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, should be equally eligible for all public positions of rank, offices, and employment according tot heir ability and with no other distinction than those of their virtue and their talent.

Article 12: Guaranteeing the rights of woman and the female citizen [citoyenne] requires the existence of a greater good; this guarantee must be instituted for the advantage of all, and not for the private benefit of those on whom it is conferred.

Article 16: Any society that is without guaranteed rights and separation of powers, is without a constitution; a constitution is void if the majority of individuals comprising the nation has not cooperated in its drafting.

Her most famous article is number 10:

No one should be hounded for their opinions, however radical;

Woman has the right to mount the scaffold. She should equally have the right to mount the rostrum,

Provided that her actions do not disturb public order as established by law.6

What Olympe meant is this: women can be tried and punished in a civil society - no one thinks that society should keep a guilty woman from mounting the scaffold. But by that same logic, women should also possess the right to participate in and build that same society by mounting the speaker’s podium or tribune, to make her voice heard in a governing body.

If they can be punished in society, in other words, shouldn’t women also have the right to lead?

Olympe de Gouges wasn’t condemned to die for her feminism, although the Republic was growing increasingly hostile to women’s political activities.7 It is clear, however, that Olympe was condemned for speaking her mind which, she believed, women had the right to do. In the late summer of 1793, she prepared to publish a pamphlet that called for free and fair elections. She attacked the Republican government for its hypocrisy: the Republic claimed to rule for liberté, égalité, fraternité, but its autocratic and violent methods had devolved into yet another form of tyranny. If this is truly a people’s government, said Olympe, let the people choose what form of government they want.

But she never had the chance to publish the pamphlet. The wife of her printer denounced her to the authorities. After several months in prison, some of which she spent in isolation, Olympe endured her trial, then faced the crowds and the guillotine.

Olympe de Gouges wasn’t the only person in late eighteenth-century France to argue for women’s rights. But despite good faith lobbying by powerful voices, female and male, the idea never gained currency, and the French Constitution of 1791 made no provisions for women’s civic equality. Under this Constitution, women were not full legal citizens.8

After Olympe’s execution, the Revolutionary press mocked her as hysterical, a woman who did not know her place and who had lost her mind. Rumors circulated that she had been illiterate and that others wrote on her behalf. Generations of historians followed suit, dismissing her as a prostitute or a courtesan, and overlooking her activism and philosophical ideas, until the late 20th century. That is when French scholars began to take a closer look at her life and writing.

As for women’s civic rights, that ended up being a much longer fight than Olympe ever would have anticipated: French women were not granted the right to vote for another 150 years.

You read that correctly. French women could not vote until 1944.

🎧🎙️Last month, I had the pleasure of speaking with Ann Foster of

about Olympe de Gouges and the French Revolution on her podcast. You can listen here.🔗And for a great resource on Olympe de Gouges, including English translations of many of her works by the playwright Clarissa Palmer, check out this page.

John R. Cole, Between the Queen and the Cabby: Olympe de Gouges’s Rights of Women (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011).

“Olympe” was her mother’s middle name.

It needs to be said that Olympe de Gouges’s abolitionist ideas come off as rather backwards to modern readers. But we should give her credit for thinking and writing about these things in forthright ways at a time when support for abolition was still in its infancy. Many French aristocrats were hostile to abolition as they drew their wealth from sugar plantations in the West Indies.

Like many of her contemporaries, Olympe thought something close to a constitutional monarchy offered the best government for France. Because of her sympathies for the royal family - as people, if not as politicians - and her preference for a constitutional monarchy, she remains frequently depicted today as a “royalist.” But although she sympathized with the royal family, Olympe did not believe the king should retain absolutist power. She believed instead that he should reign in service to the state, his powers restricted by a governing body elected by the people. Olympe worried that executing the king would actually aggrandize King Louis and render him a political martyr. Keeping him in service to the state, on the contrary, would show that Louis was simply a man and nothing more. In what I think is her most beautiful pamphlet, Olympe offered to defend the king on the eve of his trial. You can check out the translation of that text and many others in the link I’ve included at the end of this post.

Olympe de Gouges’s Declaration of the Rights of Women (Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne) was published a few months before the English Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women.

I have taken the translations of the articles from a handy little book published by Hachette in 2018. Assembled and edited by a team, the book - not much more than a pamphlet itself - includes both Olympe’s Déclaration translated into English and the United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. You can find it here. Olympe’s fight continues to this day.

Although it remains unclear whether her radical ideas and public profile made her an easy target for a government who wanted to set an example. Shortly after Olympe’s death, the government shut down all women’s political clubs and declared them illegal.

The French Republic did grant the women the right to initiate divorce, which was a huge win. Napoleon, however, restricted that right severely with the Civil Code of 1804 - a step backwards for women.

"Woman has the right to mount the scaffold. She should equally have the right to mount the rostrum." Reading about Olympe's demonization by the press and historians, who labeled her a hysterical woman triggers subversive thoughts as I watch the courts strip away women's rights to reproductive health and dismantle systems that protected voting rights for so many people. We are now living under a system that defines women according to our willingness to support racism, patriarchy, and greed, placing us squarely on top of a metaphorical scaffold. We are either rewarded for complying or punished for rebelling. Perhaps we will build enough momentum to stage a revolution here, although, in honor of Olympe's concerns, one less violent than the French Revolution and one that guarantees equality for ALL women.

One of my faves <3