First, conjure up a mental picture of Joan of Arc. When I say “Joan of Arc,” what do you see?

Now, take this poll.

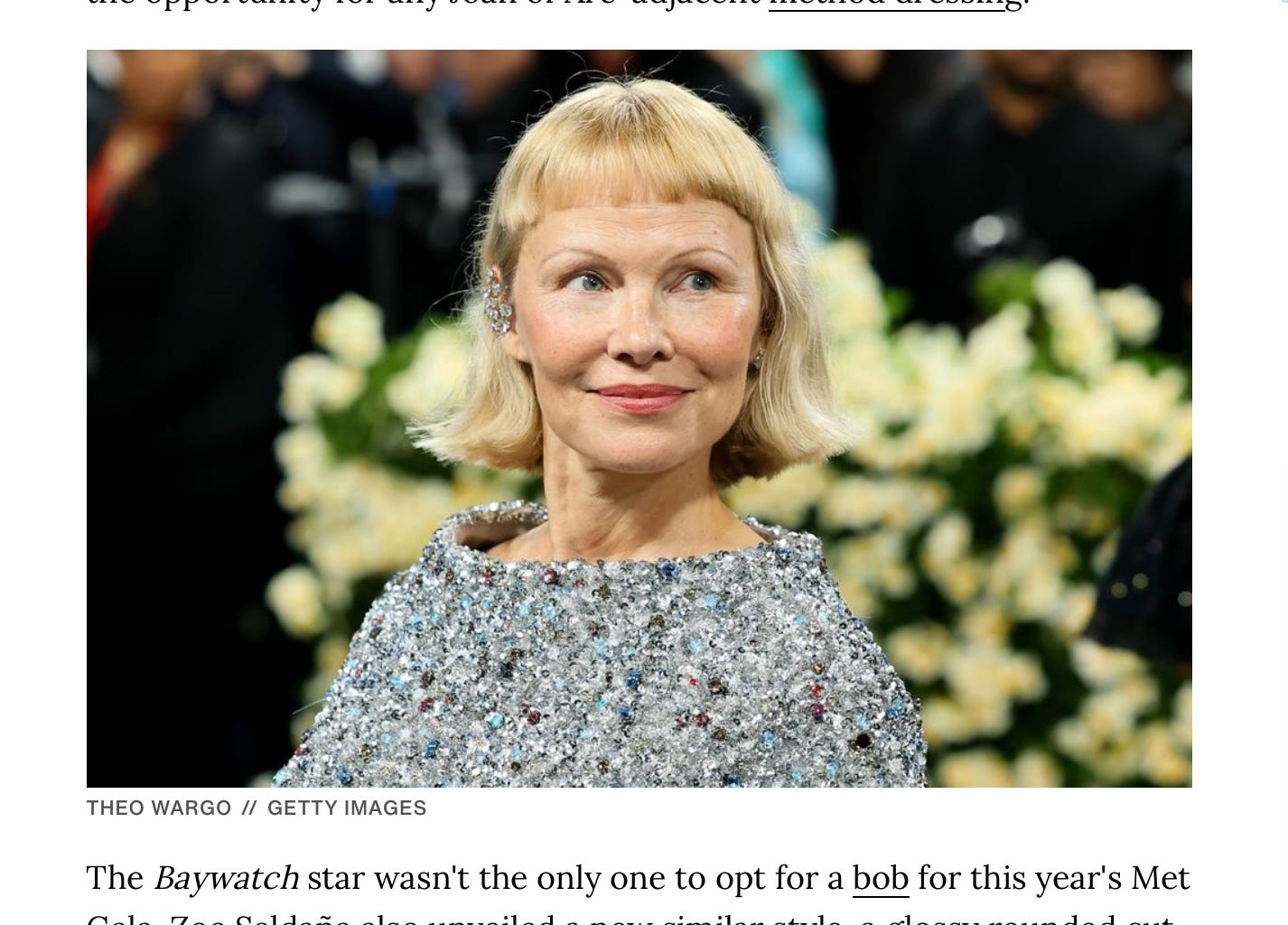

At this year’s Met Gala, Pamela Anderson sported a new coif that, according to Hannah Thompson of Harper’s Bazaar, vividly recalled images of Joan of Arc with her “microfringe” and “jaw-skimming length.” I have been as fascinated as everyone else by Anderson’s embrace of middle age through a shift in her looks. Through artful and deliberate dressing, Anderson has refocused the gaze (and the camera) away from her décolletage and toward her face. She’s kept the pencil-thin brows but pared down her makeup.

And now, with her new bob, Anderson has rejected the complicated and frilly romance of updos and tendrils, and opted for simplicity. The hair is a frame for her open and honest face. It’s a no-nonsense yet chic cut. Practical. Powerful. A hairstyle for a face that has nothing to hide.

It’s all very Joan.

“Anderson's look was also unmistakably reminiscent of depictions of Joan of Arc, whose hairstyle — characterised by her micro fringe and jaw-skimming length — was memorialised in a portrait by Albert Lynch in the early 20th century.” ~ Hannah Thompson, Harper’s Bazaar, May, 2025

Except that Joan of Arc didn’t have a bob haircut.

Now, Joan did wear something close to a micro fringe, but that was only because all of her hair was cropped short. Very short.

In fact, Joan wore something closer to a bowl cut, the kind of haircut that was popular among the young soldiering men of her time. Rather than a bob, the cut looked like this:

So why don’t we remember Joan in this way?

Before 1429, Joan did wear her black or dark brown hair in long tresses, which she pinned up or braided while helping her mother with chores in their village of Domrémy.

But when she was seventeen years old, shortly before she travelled to meet the French dauphin Charles (the future Charles VII) at Chinon in March of 1429, Joan decided to cut her hair.

When Charles first set eyes on her at Chinon, he saw a girl with “short black hair, wearing a black tunic,” a girl who already looked strikingly different from any of the young women at the royal court.1

Joan had practical reasons to lop off her hair.2 She needed to accomplish her mission: as she told Prince Charles, her objective was to lift the siege at Orléans, then escort him to Reims where he would be crowned King of France, in defiance of English claims to the French throne.3 War demanded practicality. Joan needed to keep her hair clean. She needed to keep it out of her face. She needed to blend in with the other soldiers so she couldn’t be easily identified by the English enemy.

And Joan most definitely needed to distinguish herself from the women who were usually associated with armies: camp followers, or prostitutes, whose behavior Joan roundly condemned.4 Joan didn’t want her male companions to get the wrong idea. She also wanted the French cause to be associated with purity, with virginity - her own virginity. Her short crop stood in stark contrast to the long, seductive locks of the camp followers. Joan wasn’t on the field for sex. Instead, she was sent there by God, for king and country.

Joan claimed the idea for her haircut came from her divine voices — the voices of Saint Michael, Saint Catherine, and Saint Margaret — who inspired her mission. These divine voices told her to take off her dress and put on men’s clothing, and to order a suit of armor. Her voices also told her to cut her hair.

To all evidence, Joan kept her hair short the entire time she campaigned with the French army (more properly known, in this historical context, as the Armagnacs). As the months unfolded, she must have clipped it while in camp; perhaps she enlisted the help of other soldiers to keep it trimmed at the fringe and shaved at the nape. Her hair was short as she successfully lifted the siege of Orléans and led the dauphin to the Cathedral at Reims where he was, at last, crowned King of France — mission accomplished.

Joan’s hair remained short even as she stopped hearing her divine voices after the coronation; in spite of their silence, she continued on campaign with the Armagnacs, now determined to liberate Paris (where she was defeated). Her hair was still short when she headed to nearby Compiègne, which she tried to seize from the Burgundians, allies of the English who had taken the town.

Joan’s hair was still clipped short when she was captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, then transferred her to a prison in Rouen to be tried for heresy.5 Joan remained in that prison for almost a year before she was brought to trial.6

Joan’s captors forced her to abandon male clothing and to wear a dress. Presumably, they also deprived her of the scissors she needed to cut her hair. As a young healthy teenager, Joan had hair that probably grew at a rate of half an inch to an inch every month. Which means that, after a year in prison, Joan’s hair probably did approach a jaw-skimming length.

In other words, the only time people would have seen Joan with something close to a Pamela Anderson bob was when she was brought to the stake in Rouen on May 30, 1431 to be burned as a relapsed heretic.

I want to be clear about one thing here: it is challenging to discuss Joan’s gender identity in a historically responsible way because gender was not something that Joan called upon expressly when she spoke of her mission: she spoke first and foremost of her loyalty to the Armagnac cause and to faith in her divine voices. Among the people she encountered, Joan’s gender was not a matter of discussion.7 In fact, Joan drew her power from being known as la pucelle — The Maid — a distinctly female identity that centered itself on her youth and virginity. Joan was not like Disney’s Mulan; no one ever seems to have thought that Joan was a boy.

And yet, it must be said: while she was on campaign with the Armagnacs, Joan la pucelle certain looked like a boy.

Even so, we continue to resist acknowledging that Joan had a close-cropped haircut. We refuse to honor the fact that Joan wanted her hair to look like a boy’s.

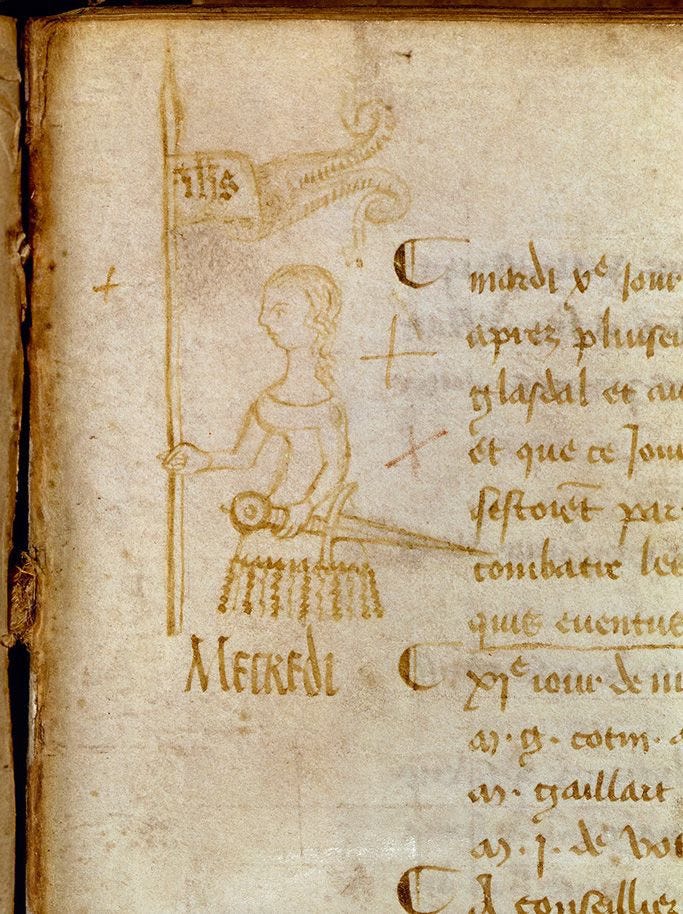

We don’t have any true-to-life images of Joan of Arc. The only surviving 15th-century depiction of her comes from a clerk who doodled in the margins while recording information about Joan’s trial.

Even that clerk never saw Joan in person. In his marginal doodle, he tried to capture a certain gender tension: how do you draw a girl who goes to battle? The clerk got a few details right: Joan holds a banner and a sword (though she claimed never to have killed anyone).8 But her armor looks like a dress with a skirt of metal plates. She has a small waist and a full bust.

And she has long hair, pulled away from her face and falling below her shoulders.

The clerk clearly tried to capture the idea of Joan’s femininity as he imagined it. How else to capture the idea of “girl” other than with skirt, breasts, and long hair?

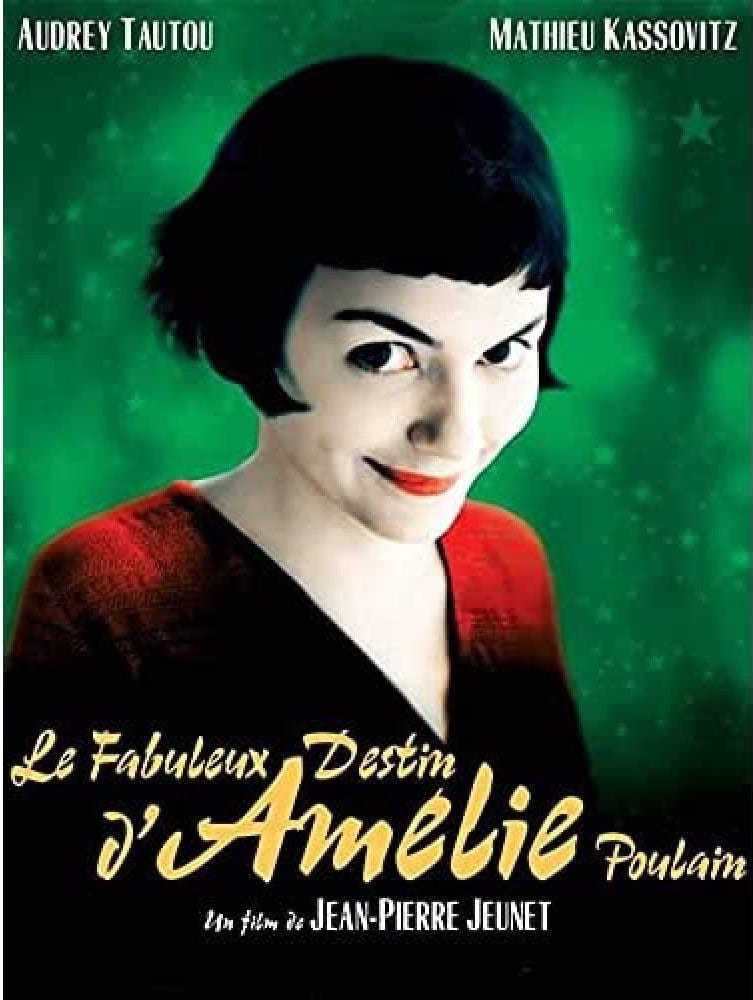

In the 6 centuries since, most artists seem to have abandoned Joan’s close crop in preference for a haircut that would clearly communicate “girl” to an audience. There are countless representations of Joan — if you take a quick look at images online, you’ll see that she most often sports that bob, looking more like a medieval Amélie than anything else.

That’s not to say that more accurate representations don’t exist. One of my favorite depictions of Joan is this late 19th-century frieze by Lenepveu in the Panthéon. Lenepveu dealt with the hair problem by covering Joan’s hair with a helmet, which is probably closer to right.

My research assistant, Sadie, pointed out that a late-medieval representation of Joan gets closer to the truth because it doesn’t overemphasize the female shape of Joan’s body, and it de-emphasizes her hair by pulling it back and slicking it against her head.

But a later famous portrait of Joan abandons any attempt at historical accuracy to indulge in 19th-century Romanticism.

I am not saying anything new. Skim the internet, read the scholarship, and you’ll find many commentators grumbling, like I am, that we’ve gotten Joan wrong. But the problem isn’t just inaccuracy. It’s that we seem to be getting her wrong on purpose. To make this point, let me tell you how I came to write about Joan in this newsletter in the first place.

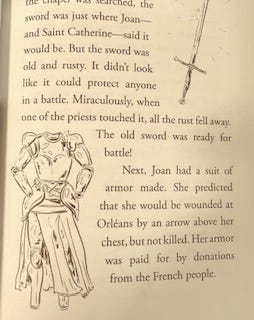

A few weeks ago, I was cleaning out some bookshelves, setting aside books that my kids had outgrown. I came upon one of my daughter’s old favorites: Who Was Joan of Arc?

Do you know the Who Was series? They are great books. Simple, story-driven histories and mini-biographies for elementary-school kids.9

My daughter loved Who Was Joan of Arc? and so did I. When I flipped through it again a few weeks ago, however, I suddenly saw how it misrepresented Joan all over its pages.

True, Joan’s hair is black on the cover, a nod to the facts. But once again Joan wears that Amélie bob, nicely coiffed from the time she first dons a pair of trousers to go find the dauphin Charles.

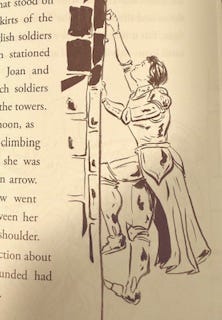

The image of Joan scaling the wall looks almost right on the hair front, but the armor seems to accentuate her bust and…wait, is Joan wearing a skirt?

That’s right, the Who Was series seems so anxious to establish Joan’s identity as a girl that they give her not only a bob but an outfit that can only be described as flouncy.

Joan doesn’t even have to be wearing the armor for the outfit to show some sass. In the image above, the armor looks like it’s striking a pose, showing a little leg. Talk about impractical. You try scaling a wall in a skirt. This is not the armor that Joan’s divine voices told her to wear. But that, it seems, is beside the point.

I showed Who Was Joan of Arc? to my daughter, now a teen, and all she could say was “ugh.”

What is going on here? On the one hand, the editors of the Who Was series want kids to understand that Joan was extraordinary in her time in part because she was a girl. Many kids might not be reading the book themselves but might instead be gazing at the pictures while listening to an adult read; I get that they need to understand Joan was a girl, to see her that way. And so the illustrations (one could argue) work hard to make Joan fit into modern versions of what “girl” looks like.

But that assumes that young children naturally see identify certain characteristics with the concept of “girl.” In fact, the book is teaching them to see girls in this way.

I can’t help but wonder if something more troublesome is going on here. Have we in the 21st century become so anxious about gender, so fixated on “girls” looking only one way and meaning only one thing that we are willing to sacrifice historical truth about clothing and haircuts? Are we so anxious about giving our kids the wrong idea that we strip Joan of Arc, once a living, breathing person who died a horrible death for her beliefs, of the very things she believed were crucial to her divinely ordained mission — her clothing and her hair?

Even Joan of Arc had a cute haircut; even Joan of Arc wore a skirt. Even Joan of Arc still “looked like a girl”: is this what Who Was Joan of Arc is saying?

Why can’t Joan just wear cropped hair, “boy’s” clothes, and functional armor? After all, many kids reading the book could see themselves in that Joan. But perhaps Who Was, and many adult readers in the 21st century, don’t want them to.

✨What do you think is going on with these portraits of Joan? Let me know in the comments.

*A shoutout to my research assistant, Sadie Ford, who was instrumental in gathering research for this article.

Subscribe for more on how we skew and politicize gender both in history and today.

Which she did with a scissors, not a knife, despite what Hollywood or other representations might suggest. Scissors were invented in antiquity and easily accessible in the Middle Ages.

This was at the end of what is now known as the Hundred Years’ war.

Modern feminists would wish that Joan had been more sympathetic to camp followers, but Joan saw herself as an instrument of God, and would not condone prostitution. In this respect, but clearly not all, Joan was quite orthodox for the time period.

The English had made Rouen their headquarters in France.

The outcome of the trial was known before it even began. Although Joan was tried for heresy, this was a political trial. Of the 131 judges, most supported the English and the Burgundians over the Armagnacs.

Joan’s story, however, is full of so much mystery that her life remains open to interpretation — which I thoroughly support. Joan is one of those historical figures who can transform according to any agenda. This is why she has become a symbol of a range of groups, from the far-right in France (mostly to support a nationalistic and Christian agenda), to American and British suffragists in the early 20th century, to 21st-century feminists.

Joan claimed to have found a holy sword, then to have hidden it. When she was captured, she was using a Burgundian sword she had found on the field.

Given their target audience, they tend to brush over more controversial topics, but they have drawn countless kids to history. I generally love them.

Loved this!! Thank you Leah!

This is so fascinating! Interestingly, even when I was picturing Timothee Chalamet's hair for the Joan of Arc comparison it was at a longer, flouncier stage. Is it also that our imaginations are limited when it comes to what it actually looked like for people from the to defy norms and live in their truth? Like we can picture short but not short short?