I’ve had quite a few new subscribers in the last month. To you, and to everyone who has been with me for a while, I say - Hello! I’m so glad you’re here. If you’re enjoying this free newsletter, please click on the red “share” button at the end to send it to a friend. Clicking on the “like” button at the end also helps get my writing in front of more eyes. And thank you for reading!

This week, after attending the American Historical Association in New York City, I spent a few days at the Morgan Library and Museum in midtown doing some research in the Sherman Fairchild Reading Room. Recently, a friend wanted to know more about what it’s like to work in rare book rooms and archives. It’s a good question! I have spent decades in these places so I hardly think about it anymore. But if you don’t hang out regularly with old books and letters, you wouldn’t know.

So today, I’m give you the tiniest glimpse of a visit to the archives, based on my days at the Morgan.

First you should know: you are not allowed to take pictures once you are in the Sherman Fairchild Reading Room of the Morgan Library, at least not pictures to share on social media.1 Believe me, I asked! So while I can’t show you pictures of what I actually worked with (many wonderful gems), I can show you a bit of the process around working with rare materials to give you an idea.

Researchers first enter the Morgan through a side door — not the main entrance. There you sign in and wait for a guard to escort you to the glass elevator.

From there you travel up three floors (a short but fun trip since the Morgan is a beautiful space filled with sunlight) until you arrive at the Reading Room.2

Once you enter the main doors, you check in at reception. The lovely staff will direct you to the lockers where you will stow most of your belongings.

Like most archives, the Morgan’s Reading Room has a few rules:

Stow all your outer wear in the locker, including coats, hats, and scarves. Reading rooms are often quite cold in order to protect the materials, so you’d better wear layers and a sweater, because you can’t bring that scarf in.

No pens. Only pencils.

Laptops are fine as are charging cords. But no cases for those laptops.

Notebooks are acceptable in the Morgan. I’ve been in some reading rooms where they prefer loose paper rather than notebooks with covers.

A rare book librarian’s greatest fear is that a researcher will steal something, stowing it away in a laptop case or notebook. This is why you can’t bring cases and, in some archives, you can’t bring notebooks.

Finally, the reception asks you to wash your hands just before you enter the main reading room. All archives want you to work with clean hands. But the Morgan is so careful about it that they’ve installed a sink right next to the lockers.

After you step into the reading room, you sign in yet again. The librarian then shows you to your desk. Once you’re settled, they bring you the items you requested, one by one. After you finish with each document, the librarian retrieves it, signs it back into the catalog system, then signs the new item out before bringing it to you.

These objects — documents of all kinds, letters, manuscripts, old books, engravings, and more — are precious, so the librarians take the utmost care to make sure every document is properly signed in and out. If you have multiple documents to look at, as I did, the entire process takes hours.

Real panic ensues if a document is not where it is supposed to be. This happened to me during my trip. A letter I had requested — an extremely historically significant document, and one of the principal reasons I had come to the Morgan — was not in the file. I could see the look on the librarian’s face shift: she was concerned that I wasn’t getting the material I needed, of course, but I suspected she was mostly worried that the item had gone missing.

Where was it? Maybe in the exhibition on Belle Da Costa Greene downstairs? Was it in a different file? You could practically see the librarian’s mind race to the worst-case scenarios.

An email immediately went out to all the curators with several staff cc’d.

I felt immensely important for having alerted the librarian to the missing document.

A couple of hours later it became clear that the document was indeed in the Reading Room (giant sigh of relief) but it had been misfiled in a different folder. The folder was quickly located. The librarian made a note of the mistake, signed the document out to me, and brought it out to me at my desk.

Behind the desk staff chatted about the mistake for the next hour, updating each other on what happened. Stories were traded about missing documents, sneaky and conniving researchers, thieves who pilfered librarian’s keys, stealing them right off the desk to make duplicates overnight, then returning said keys with the librarian none the wiser — at least not until items went missing.

In the meantime, I looked at the newly found document, which seemed all the more precious because it had almost been lost. It was fabulous: Charlotte Corday’s last letter, written hours before she was sent to the guillotine during the French Revolution. I wish I could show it to you. All I can say is that the letter, a mere scrap of white paper with a few lines, taught me so much about Charlotte and about that moment. Gazing at her composed handwriting, feeling the featherweight of the paper in my hand, I could practically hear her voice. I was there with her, in her prison cell. She was calm. I could see it in the letter.

The last, all-important step before leaving for the day: open your laptop and notebook for the librarian to show that you aren’t stealing any of the materials.

And those, my friends, were how I spent my days at the Morgan Library. These are the kind of days that make me feel insanely lucky to do what I do.

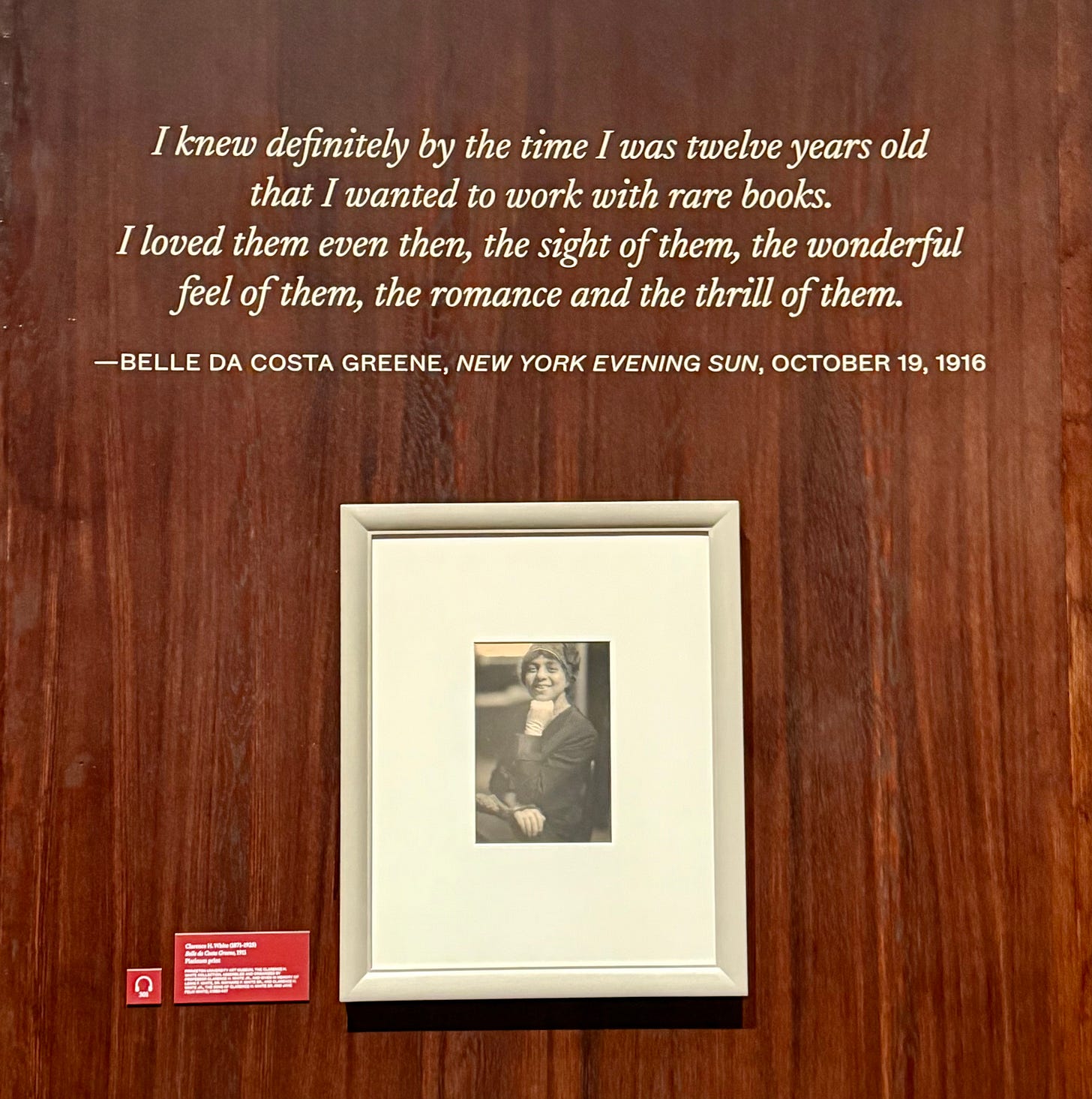

And there was one more perk. Since I had an appointment in the Reading Room, I received free access to the fabulous exhibit on Belle Da Costa Greene on the first floor. Belle Da Costa Greene was J. Pierpont Morgan’s librarian. You may know of her from the novel The Personal Librarian by Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray. Much of the Morgan’s collection is due to Greene’s deep knowledge of European history and its material culture, her keen eye, her savior-faire in cutting a deal and chasing a precious object.

She almost single-handedly built one of the most important private collections in the world. There is much more to say about Belle Da Costa Greene, and I will write about her soon.

In the meantime, though, I have to thank her. She, and other librarians like her, have made my life’s work possible.

You are allowed to take pictures of documents but for research purposes only. If you want to publish or share on social media you need to order an official copy well in advance. The demand is high, and although the reproduction staff is hard at work, it can take months for them to get to your order. This is quite common for archives.

You might get kicked over to Substack’s site to watch this video. For those who don’t already have an account, though, you may be able to download it. Just a little view of my trip to the third floor.

Charlotte Corday’s final letter! I’m intrigued what you’re up to that got you looking at that (though if I had the chance, I’d go see it too!)

I've been to many archives but nothing this elaborate in terms of rules and a sink by the lockers! There's a photograph of the librarian I wrote about in my first book, Regina Anderson Andrews with her assistant Edna Law--one of the first Chinese American librarians at the New York Public Library in the Belle Greene exhibition.